November 7, 2025

HF Case Files: Three Mile Island

On March 28, 1979, a small malfunction at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, set off a chain of events that would bring the United States dangerously close to a nuclear catastrophe. Within hours, half of the reactor core had melted. There were no explosions, no mushroom clouds, just a slow motion disaster playing out quietly in a control room.

This story isn't just about equipment failure; it's about how design, training, and human decision-making came together in all the wrong ways. In this blog, we'll explore how human factors—that is, the science of designing systems that work with, rather than against, human performance—broke down in the infamous Three Mile Island accident.

Setting the Scene

Three Mile Island sits on a narrow strip of land in the middle of the Susquehanna River. Back in 1979, in the midst of the optimism of the nuclear era, it was one of the newest and most modern nuclear power facilities in the country.

On the night of March 28, the Unit 2 control room was calm. The night-shift operators monitored hundreds of gauges, switches, and blinking lights. Everything was running smoothly until about 4 a.m., when a small problem appeared in the plant's cooling system—one which would eventually snowball into one of the most serious nuclear incidents in U.S. history.

Inside the Cooling System Breakdown

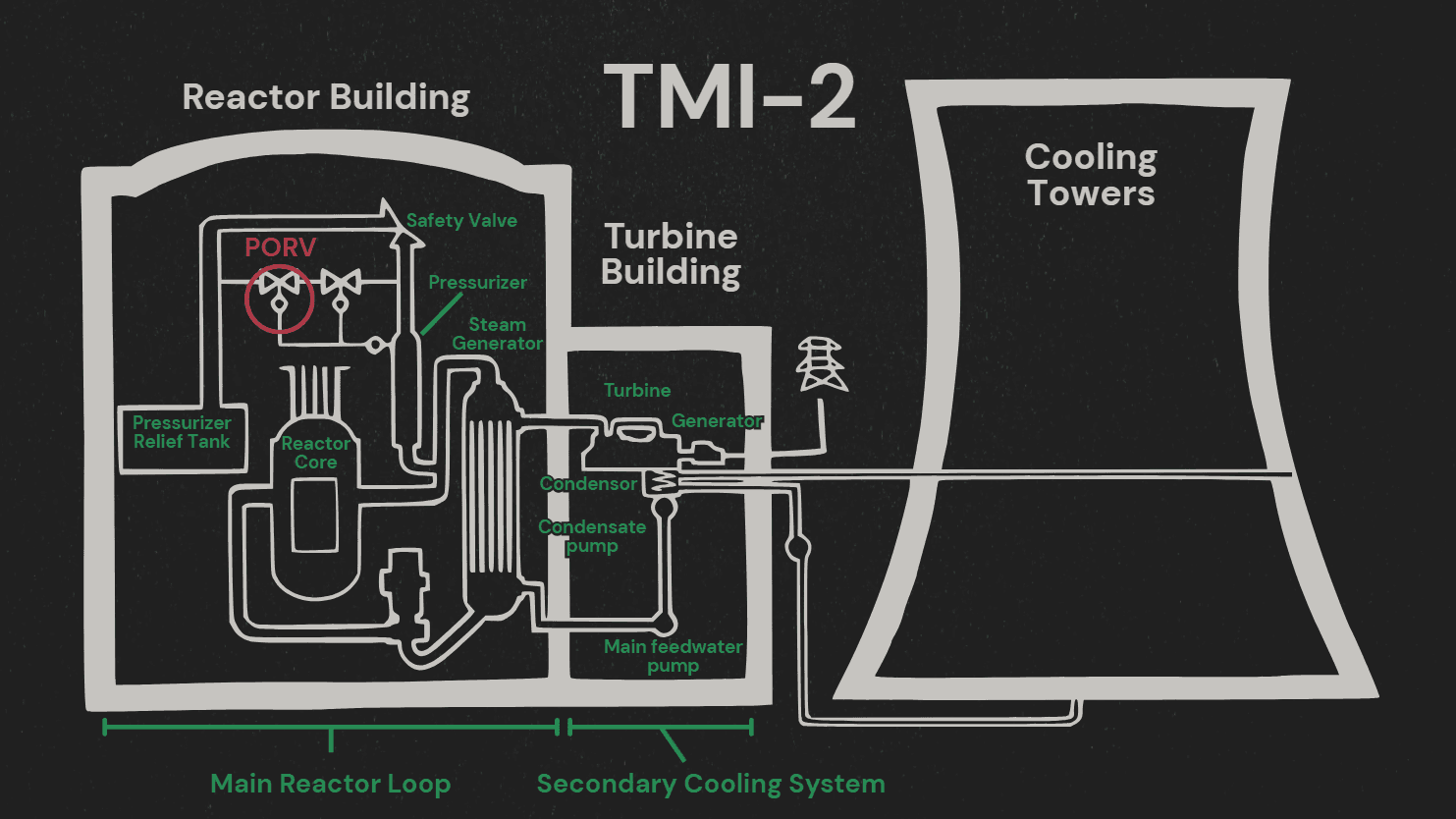

That issue began in the plant's secondary cooling system, which functions much like a car radiator: expelling heat so that the reactor doesn't overheat. When that system faltered, temperature and pressure inside the main reactor loop started climbing.

A built-in safety response was supposed to manage this: a relief valve on top of the pressurizer, known as the Pilot-Operated Relief Valve (PORV), would open automatically, vent out some steam to relieve pressure, and then close again. This time, however, it didn't close—the valve became stuck open, allowing coolant to quietly escape.

As pressure dropped, the control room was suddenly flooded with dozens, then hundreds of blaring alarms. In the midst of the chaos, operators noticed a gauge suggesting the water level was rising, so they slowed the emergency cooling flow to prevent overfilling—exactly as they had been trained to do.

In reality, the exact opposite was happening: steam bubbles had fooled the sensors into showing a high water level when, in fact, the reactor was running dangerously low. For nearly three hours, the valve remained stuck open, and coolant continued to drain out as the operators acted on a completely incorrect picture of what was happening.

By the time they finally realized the valve hadn't closed and manually blocked it off, half the reactor core had already melted. The unit was shut down and the incident became the most serious accident in U.S. commercial nuclear power history.

A Closer Look at the Human Factors

Even though a valve failure triggered the event, the lengthy delay in recognizing what was actually happening was driven by three key human factors issues: alarm flooding, misleading indicators, and flawed mental models.

Alarm Flooding

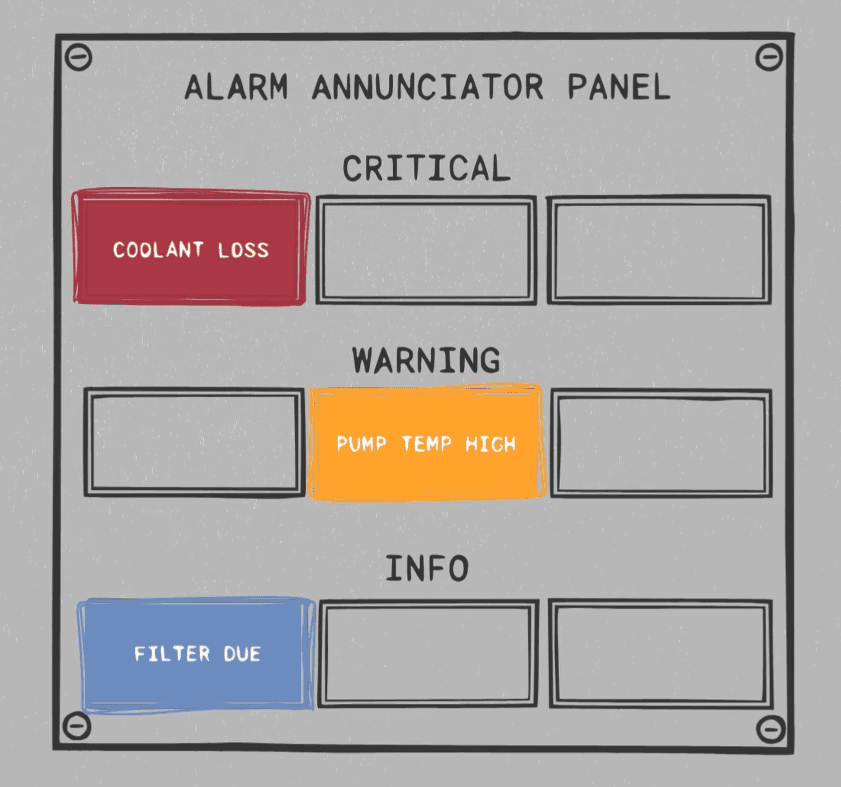

In total, about 750 alarms went off during the incident. That’s not a typo—seven hundred and fifty. Imagine trying to make sense of hundreds of flashing lights and blaring sounds, all competing for your attention in real time, while a nuclear meltdown is in progress.

Ideally, critical alarms should stand out, either visually, audibly, or both, so that operators can identify and prioritize what's most urgent. At Three Mile Island, however, every one of those 750 alarms looked and sounded the same, making it impossible to distinguish (and, in turn, prioritize) between alarms indicating life-threatening failures and minor deviations.

This is called alarm flooding; it overwhelms operators, reduces situational awareness, and often leads to essential warnings being missed entirely, which is precisely what happened at Three Mile Island.

Misleading Indicators

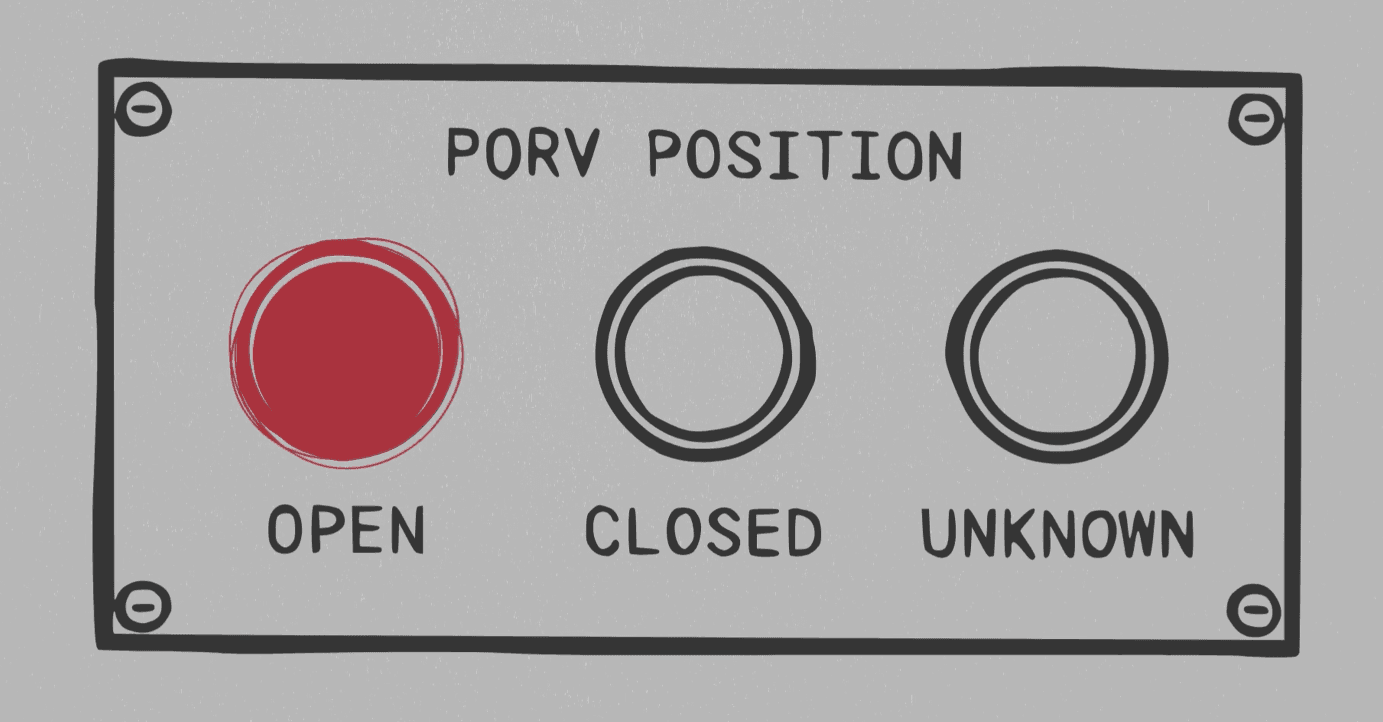

One of the most consequential design flaws was the indicator light for the PORV. When the control system sent the signal to close the valve, the light would turn off, seemingly implying that the valve had been successfully closed.

However, that light wasn't actually showing the position of the valve; it was actually showing that a "close" command had been issued. In other words, it confirmed that the system had told the valve to close, not necessarily that the valve actually did close. In the case of March 28, the light had turned off, so the operators had incorrectly assumed that the valve was shut.

Inadequate Training and Faulty Mental Models

The operators weren't careless and had, in fact, followed their training throughout the course of the incident. It turns out, however, that their training hadn't prepared them for this particular failure.

Case in point: the operators were taught to avoid overfilling the reactor, so when the gauges appeared to show rising water levels, they did what they were supposed to do, which was to reduce coolant flow. The real danger, though, unbeknownst to them, was the opposite. The system was losing water, not gaining it.

This mismatch between what the system showed and what was really happening shaped the operators' mental model. Once they formed that initial understanding—that the valve was closed and the reactor was too full—they subconsciously filtered all new information through that lens. This phenomenon is known as confirmation bias: favoring information that supports your first conclusion and dismissing anything that challenges it.

How it Could Have Been Prevented

So, the question becomes: how could human factors have changed the outcome at Three Mile Island? Here are some ways we might have been able to prevent the partial meltdown with improved human factors.

Clear, Direct Feedback from Interfaces

The PORV indicator light was one of the most damaging design flaws in this incident. It turned off when the "close" signal was sent, not when the valve was actually closed, violating a basic principle of human factors design: the absence of a signal should never be used to mean "everything's fine".

Instead, systems should display the actual status of critical components, not just the last command sent. In this case, a feedback system confirming the valve's true position—open, closed, or unknown—could have immediately indicated the problem.

Prioritized Alarms

With hundreds of equally loud alarms sounding at once, the operators couldn't tell which ones they should attend to first. A better alarm system would prioritize critical warnings by using color, sound, or placement to differentiate the most urgent alarms from routine ones. For example, in this case, one large flashing message could read "LOSS OF COOLANT" in bright red to draw operator attention over all other, less critical alerts. This prioritization system would help operators focus on what's actually threatening the system.

Redundant and Cross-Checked Sensors

Steam bubbles tricked the water level gauge into showing that the reactor was too full (when it was, in fact, dangerously empty). Redundancy is key in preventing this kind of misleading data. Multiple independent sensors using different measuring methods can help cross-check and validate readings. Even simple logic checks—like flagging impossible combinations such as “water level high” and “pressure dropping fast”—can prompt operators to re-evaluate the data before acting on it.

Training for the Unexpected

The operators at Three Mile Island weren't unskilled—they just hadn't seen this kind of scenario before. This is why simulation-based training is so important: it allows operators to learn how to recognize when something doesn't fit the expected pattern by practicing those failure scenarios in a realistic manner. This helps them build flexible problem-solving skills instead of relying solely on rigid textbook procedures.

Smarter Procedures and Checklists

Procedures can also serve to combat faulty mental models and cognitive biases. Requiring operators to verify any major system change through two independent sources before acting on it could have helped them to catch the open valve much earlier.

Lessons Learned

None of these fixes would have required a complete overhaul of the nuclear power industry—in fact, they're actually just straightforward human factors improvements. Implementing better displays, prioritized alarms, smarter training, and clear procedures is all it takes to make sure operators get the right information, in the right way, at the right time. After Three Mile Island, that's exactly what the nuclear industry did; control room interfaces were redesigned, alarm systems were rethought, and operator training became more rigorous. But it shouldn't have taken a partial meltdown to spark those changes.

Why This Matters

At HF Designworks, this is the kind of challenge we tackle every day: reviewing complex systems, finding hidden risks, and, ultimately, ensuring people and technology work together safely and efficiently.

To this day, the Three Mile Island accident remains one of the clearest reminders of what could happen when human factors aren't centered. If you're working on a system that could benefit from a human factors review, learn more about our capabilities at [homepage or Services link] or contact us at [Contact Form link].

To explore this topic further, you can also read HF Designworks CEO Scott Scheff's co-authored paper on nuclear power plant regulations here.

This article is part of our ongoing series, HF Case Files, where we examine well-known accidents through the lens of human factors. You can also watch the companion video for this case on our YouTube channel.

Keep Reading

// SAY HELLO

Contact

HF Designworks, Inc.

PO Box 19911

Boulder, CO 80308

(720) 362-7066